Inviting AI to participate in our world

This post is my research new year's resolutions for 2026. Soon after completing my PhD I already started thinking about the next step – how to bring my experience in telerobotic puppetry to AI research. Now, I have gathered enough insight to formulate a research position that would guide me through the upcoming postdoctoral years.

TL;DR

To steer away from the current unsustainable and parasocial direction that AI is heading in, we need a shift both in the foundation of the technology and in how we use it. The Thousand Brains Project showcases a non-deep learning architecture, from which true bio-inspired intelligence could emerge. However, it is not yet designed to scale. Predictive world model architectures such as JEPA open a first corridor out of the inefficient and unreliable generative paradigm, but lack continuous learning. Inspired by the Thousand Brains model, could we apply a distributed learning architecture such as LatentMAS to JEPA?

To evaluate true intelligent machines, we should pull them out of their abstract language bubble and invite them to the world and into our society. I argue that the medium of puppetry is a perfect gateway. As I have shown in my PhD, the puppet theater is both a fun tool for the community to discuss sensitive issues, as well as a restricted and controlled physical environment for integrating affective technology. Using video training coupled with language (VL-JEPA extension) and action-conditioning (V-JEPA 2-AC), can we invite autonomous puppets to participate in co-creation?

Resisting the parasocial

While exploring how technology could be a positive factor in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, I found that I need to resist the global trend of virtualizing human relations. Most of Israelis and Palestinians have never met a person from the other group, yet they formed their (largely negative) relation in a one-sided way, through media and culture. At the opposite end, technologists were trying address the conflict yet-again in a one-sided manner, creating virtual experiences that try to evoke empathy by taking the perspective of the other, without actually including them in the process. My alternative was to use the traditional artistic practice of puppetry: a communal ritual of empathy and collective action, and augment it with telerobotic technology that can extend the performance across borders.

The hippo and parrot play (TOCHI paper).

The hippo and parrot play (TOCHI paper).

Relationships that are formed one-sidedly are defined as “parasocial” relationships. As I see it, technology is consistently driving humanity into that abstract and fake dimension. What started as a commercial effort to capitalize on human social psychology, getting us addicted to Facebook feeds and to watching that WhatsApp “seen” status, has now evolved into an absolute abstraction of the human connection with the advent of Large Language Models (LLMs), our new AI Chatbot friends. Consequently, The word “parasocial” was declared as the 2025 word of the year by the Cambridge dictionary.

The illusion of empathy

Theoretically speaking, an AI agency could co-exist with humans as an active participant. LLMs are increasingly invited into our lives as collaborators, advisors, and friends in-need. However, the current technology behind dominant LLMs does not have the capacity for a real connection. Being 'stochastic parrots', LLMs are good at creating the illusion of empathy, but that's where it ends.

Below, are the major reasons for why this happens with LLMs:

No learning

Broadly speaking, massive deep learning models do not learn anything new during an interaction. The learning process is too computationally expensive and has to be done offline. Instead, they store and recall information by appending it to every prompt that they receive. This is analogous to the method used by Leonard, the protagonist of the film “Memento”, who tattoos information on his body to compensate for his chronic amnesia. Therefore, any semblance of learning in a conversation is false.

Memento

Memento

No grounding

Generative models such as LLMs and VLMs (Vision Language Models) are essentially highly sophisticated auto-complete machines with some level of randomness. They process massive amounts of text into tokens, sort them with context-relevance using a 'self-attention' mechanism, and predict the next token in a sequence (can be a word in a sentence or pixels in an image). Once the the next token is predicted, the following token can be predicted based on the new sequence. This is called an autoregressive function.

Our brain does not work like that at all. We have no use in replicating the world around us to the pixel or word level. Instead, we construct an internal, abstract, representation of the world and predict how it might change in response to different events. In the realm of deep learning, this means predicting in the latent space, the space of representation. When we see a glass falling off a table, we don't need to visualize in our head millions of glasses falling off a variety of tables and exploding in different directions. We have a grounding in physical space. We have a general prediction of what happens to glass objects when they fall, and when we see it happen we can verify it. If something seemed to act differently than what we expected, we correct our predictions.

When you have no grounding in a reality, and instead you operate in one big floating statistical space, you are bound to hallucinate. you act as if you are part of a consistent reality, but in truth you are detached.

Not 'open to the world'

“This world is not what I think, but what I live [ce que je vis]; I am open to the world, I unquestionably communicate with it, but I do not possess it, it is inexhaustible.” Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception

If we examine prominent theories of phenomenology, cognition, and education (such as Enactivism), we quickly come to the conclusion that intelligence and sociality are inextricably bound to movement in the world. There are profound reasons to why a face-to-face meeting feels much more meaningful than a Zoom call. It is not just about nonverbal communication, but about creating a connection through what Merlau-Ponty called the intermondes, or the “interworld”. In fact, I wrote my Master's thesis about this. True learning and interaction is about participation. We figure out the relation of our body to the world and to the bodies of others through action and perception. Needless to say that disembodied and passive LLMs do nothing of that.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

A new approach

I outlined significant shortcomings, but that is not to say that there hasn't been significant progress on all of the issues above. After conducting theoretical and hands-on research, ironically, with a lot of help from the Gemini LLM (a classic case of Wittgenstein's ladder), I outline my path forward.

The Thousand Brains Project

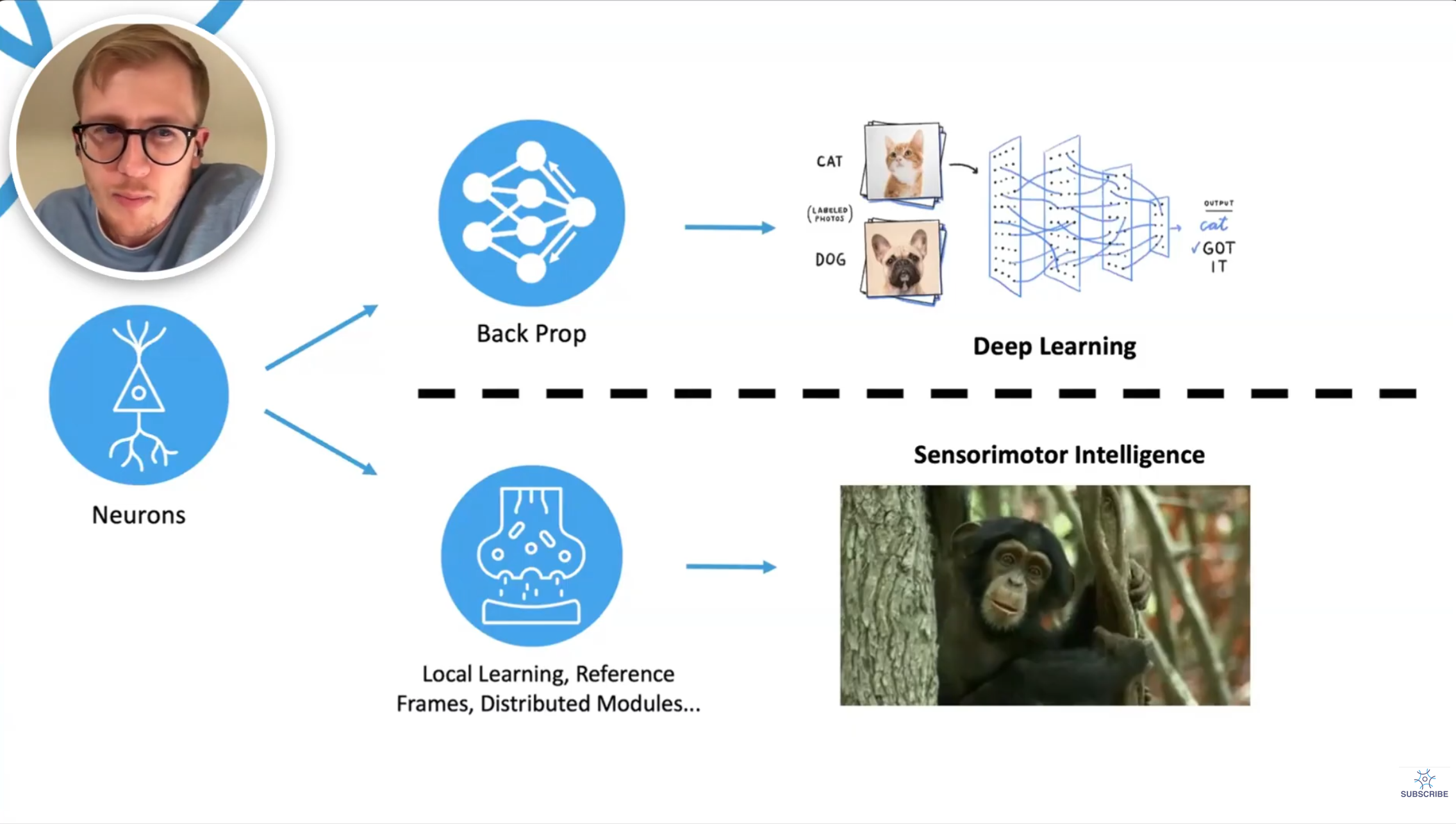

The Thousand Brains Project is a brave initiative because it challenges the paradigm on which Machine Learning research relies on: Deep Learning.

From The Thousand Brains Project.

From The Thousand Brains Project.

With its new approach, it addresses all of the issues I specified earlier:

Online learning: Deep Learning networks are only loosely based on the brain's neuron cells. They contain nodes that 'fire' (activate connected nodes) in response to a certain input, based on their given 'weights' (and an internal bias). The deep learning network is monolithic, designed to scale to more and more connections and weights between neurons as the input becomes complex. However, this makes the learning process so resource intensive (adjusting all of the networks' weights with a method called “back propagation”) that it's impossible to learn in real-time. In contrast, the Thousand Brains model is based on the neuroscience theory of 'cortical columns'. It is just what the name says: thousands of independent learning modules that differ in their 'reference frames' (see the next item). Each module 'votes' on its prediction (for example, “this is object X”) and the whole body reaches one consensus. This means that learning is a local process: only the relevant modules are modified, making online learning possible.

Grounding: Learning modules in the Thousand Brains system are grounded in a grid-like representation of the world in relation to a reference frame. This could be a 3D reference-frame of an object in relation to a part of our body (how it feels to a part of our body when we move it, how a part of the object visually changes when it rotates), but it could also be an abstract concept in relation to other abstract concepts or sensory inputs, such as hearing a word in a context (see this post). This means that learning is always grounded in a map of internal representations.

Sensorimotor learning: Thousand Brains learning modules always learn in relation to some movement in space and in a sensory context. A sensorimotor agent cannot learn by passively processing information. Instead, it interacts with the world, makes predictions about the expected sensory input in relation to its reference frame (“I am now touching a fresh coffee cup, it would feel warm”), and adjusts its hypothesis if the prediction is wrong.

The initiative is open source and funded by the Bill Gates Foundation. However, although the project has made significant progress, showing promising results in 3D object detection, it is still a long way from showcasing more general intelligence or contrasting existing language-based models. The developers maintain that language learning cannot be 'rushed' into the model. It should go through the same process as an infant, first developing a basic grasp of the world, then basic sounds, phonetics, and finally associating words to objects and behaviors in the same way that we do. This level of scale and hierarchy is still not developed in “Monty”, the project's flagship implementation. Furthermore, it is still unclear how it would handle such a scale. The type of “sparse” processing used in cortical columns is efficient for real-time learning, but it is not optimized for massive data and does not make use of the current dominating compute hardware, the GPU. The emerging field of Neuromorphic computing fits the Thousand Brains model much more than the GPU, and we might see it rise as the future of AI.

The world model: JEPA.

I began to search for a midway that could match the Thousand Brains project at least in spirit, but still produce results that can challenge LLMs. AI world models, a leading 2025 trend, are distinguished from generative models by providing Grounding and abstract Prediction, bringing them closer to biological intelligence. The majority of world models are based on Deep Learning, which, as I explained, is both a downside and an upside. I became particularly interested in the JEPA (Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture) models of Yann Lecun at the Meta FAIR lab. First, because of their commitment to open source, and second, because Yann Lecun has been a long-time vocal critic of generative models from reasons similar to the ones I outlined. The “joint embedding” aspect of JEPA achieves what I described earlier as “predicting in the latent space” and is the core difference to generative models. The model learns to predict what will happen not by reconstructing it as a text or image, but by predicting the state of the world in its own representation space.

Meta's latest foundation model, V-JEPA 2 is designed to achieve that first step of an infant, a basic grasp of the physical world. By watching millions of hours of videos and learning consistent behaviors that can be predicted, JEPA built its model of the world. This is not a training that can be reproduced without access to substantial resources, but the claim of the authors is that any behavior or capability could be developed by using the V-JEPA 2 model as a starting point. For example, the recently published VL-JEPA model attaches language to V-JEPA's world model, which enables it to answer questions about a video without any specific training for that task. V-JEPA 2-AC is an extension of V-JEPA 2 that can plan actions to achieve a certain goal state. According to the original paper, it took 62 hours of videos of robots performing tasks along with movement metadata to train a grip robot to perform arbitrary tasks. While this is not yet being “open to the world”, it combines a world model with action.

Local learning: LatentMAS?

V-JEPA 2 models are described as having the memory of a goldfish, which is not uncommon in Deep Learning. Could we endow them with something similar to the local learning of the Thousand Brains project? Here we are venturing into the unknown, but a model such as LatentMAS may provide an inspiration. Although it was designed for LLMs, it shows how multiple agents can share their latent space to achieve “system-level intelligence”. What if we could deploy a pool of thousands of small V-JEPA modules, each assigned a small perspective of the world, and have them share their latent space? Yann Lecun has recently quit Meta to form a new company, AMI Labs, that aims to create world models with a “persistent memory”. How will he do it? 🤔

Puppetry as a lab

I started this post by describing my resistance to the parasocial through the integration of technology with the artistic and communal practice of participatory puppetry. The puppet theater proved to be a great lab for telerobotics. Participants with different skills and expertise could dive deep into robotic engineering to realize their creative vision. The operation was simple, using a glove sensor and a maximum of three actuators, and the expressiveness of the robotic puppets was endless.

Telerobotic puppetry (TOCHI paper).

Telerobotic puppetry (TOCHI paper).

I now seek to invite AI into our world by inviting it to participate in puppetry. The theater is a restricted environment with relatively few degrees of freedom, but when combined with language, puppets can accurately depict complex and emotional scenarios from the lives of humans. Could VL-JEPA models be trained to navigate the puppet theater? Could they plan their robotic puppet performance based on examples and feedback from the audience and the co-actors? Could they surprise us with an unbiased creative insight just like a child would? Could they have some form of learning using a distributed latent space? These are the questions that I'm aiming to explore.

Read this blog on Mastodon as @softrobot@blog.avner.us